It’s a law of economics that, over time and with perfect competition, the price of a product tends to approach the marginal cost of the product — that is, how much it costs to make one more item.

The marginal cost of a virtual good is just about as close to zero as you can get. Sure, making the first one can cost a great deal in terms of labor and design costs. But once you’ve done that, all future copies are, in effect, free to produce.

Consider land-based radio programming. It takes quite a bit of money to create the content, put up the radio transmission tower, license national programs, pay the utility bills. But once all that’s done then the difference in cost to the radio station between 10,000 listeners and 10,001 listeners is zero. The same goes for broadcast television.

After all, if you’ve got two stations, both charging for content — say, by encrypting broadcasts and renting out decoder boxes — one station can drop its price in half and double its audience — at no additional cost.

By comparison, newspapers cost money to produce and deliver. But even here, when marginal costs get low enough, they can be distributed for free. Many local newspapers like the PennySaver chain, as well as trade publications, are distributed for free because the advertising revenues for each new reader are higher than the marginal costs of producing and distributing the publication. Online publications are free for the same reason — not because they don’t cost anything to produce, but because they can reach out to a much larger audience at very little additional cost.

Customers usually have a pretty good idea of what the marginal cost of a product is. They might not be able to say down to the penny what a CD costs to print and distribute, but they know that the MP3 copy costs a lot less. It doesn’t matter how much the product originally cost to create — its all about the marginal costs. Television programs are very expensive to produce, but people expect to see them for free.

Virtual goods designers often forget this, focusing on how much time and effort they put into creating their content. Unfortunately, that only applies to the first item they create. The second copy of the item has almost no cost at all.

Virtual goods, are caught directly in the grip of the marginal cost vise. If I have half the market with my $5 chairs, my competitor can drop his price to $2.50, take over all my customers and drive me out of business — and come out even. Then someone else will come along and under sell him, until the price winds up as close to zero as no nevermind.

Not to mention all the competition from freebies.

But that does not mean that virtual designers are doomed.

Here are five strategies to beat the marginal cost price trap.

1. Sell ads

There are two key principles to profitable advertising. One is to keep marginal costs of new goods lower than the increased advertising revenues for each new customer. This is easy if the marginal cost of each good is zero.

The other principle is to have enough of a reach that your per-customer advertising revenues add up to a sufficient amount to cover your initial design and marketing costs.

This is a tricky thing to achieve, given the highly fragmented nature of the Second Life marketplace — and the even more fragmented OpenSim markets.

However, as the virtual worlds continue to grow, this will become more practical. We’ll be seeing furniture and clothing with corporate logos as well as stores full of completely free, unbranded merchandise — but you have to look at advertising while you shop.

Advertising is already used to fund radio and broadcast television — even race cars. And, especially in television, the content production is extremely expensive. And most online publications are currently funded exclusively by advertising.

Advertising-supported models might work for venues such as coffee shops or freebie malls or race tracks, or for virtual publications.

Keep in mind that advertising sales requires a very specific set of skills — it’s not enough just to announce that advertising space is available. You have to go out and find the advertisers, then work with them to ensure that the ads are effective.

2. Have a brand monopoly

Free markets tend to frown on monopolies, but there is one area in which monopolies are perfectly legal — the monopoly over your own, copyrighted content. On your brand.

Madonna, for example, has a monopoly on new Madonna songs and videos. Sure, I can put my underwear on outside my clothes and try to copy her, but everyone will see me as what I am — a cheap, generic knock-off. If I try to steal her content and redistribute it, the law is on her side, and the authorities will eventually catch up with me and shut me down.

Creating this kind of a legal monopoly requires excellent branding. I would pay for a Harry Potter book by J.K. Rowling. But I would expect to read Harry Potter fan fiction by unknown writers online for free, because the unknown writer has no brand-name recognition.

The are plenty of examples out there of cases where the brand is worth more than the underlying product. I, personally, pay a premium for Diet Coke instead of drinking generic soda — even though, in a blind taste test, I probably couldn’t tell the difference.

Lots of people pay huge amounts of money for brand-name diamonds even though generic, man-made alternatives are cheap and indistinguishable from natural ones to anyone who isn’t an expert. And, often, even the experts can’t tell the difference. They’re paying money just for the brand.

In virtual worlds, you can build a brand not only through all the traditional means — advertising, social media, public relations — but also through building relationships with your customers. Invite them to virtual events, give them exclusive previews of new content, provide excellent support.

Make sure your brand is clearly recognizable and that your customers know what you stand for. And leverage your brand power to promote your licensed distribution channels, so that your customers know where to find the real stuff, and not the back-alley generic knock-offs.

3. Sell a subscription

We all know of platforms that take stuff that is available out there for free, package it up, make it a little nicer, and sell subscriptions to it.

Cable companies, for example. We could watch the television for free, and, depending on where we live, we could even have more than one channel. But the cable subscription offers better quality and more channels.

Or take Netflix. Prior to Netflix, people downloaded movies illegally online. But with Netflix and Hulu you get better quality, no viruses, a decent selection — and it’s super convenient.

Now Netflix accounts for the bulk of online traffic in every territory where it does business, proving that yes, people are, in fact, willing to pay for digital content.

Subscriptions work when customers would normally have to spend a lot of time or money each month on the product or service.

People subscribe to magazines, to concert series, to fitness clubs.

How could this translate to virtual worlds?

Going to clubs is popular with many virtual world residents, and many clubs have cover charges. A club subscription could get subscribers into the most popular clubs without having to wait in line or pay the cover, and they could go to as many clubs as they want. The subscription service could also help new clubs promote themselves, and the more clubs join up, the more attractive the service would be for customers.

Pets are popular in virtual worlds, and some types require regular food purchases. A subscription service would ensure that all your pets get all the food that they need, at a lower cost than buying it every month.

As virtual reality goes mainstream, we’ll see more and more products and services that could potentially be sold via subscription.

4. Sell convenience

Speaking of convenience — that, by itself, can be a business model.

Apple’s iTunes, for example, made it so easy to buy and enjoy music that it helped the iPod crush all of its competitors.

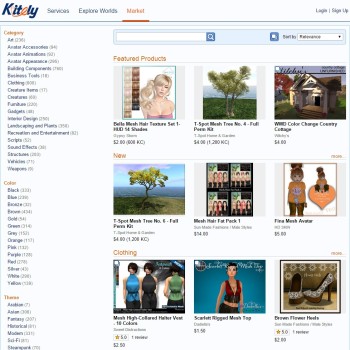

Today, the Kitely Market is trying to do the same for virtual goods.

As virtual reality expands, keep and eye out for products and services that are difficult to find or use. If you can come up with a way to make them more convenient and easy, you could have a successful business.

5. Sell less stuff

It might seem crazy, but there are times where you can actually make more money by selling less stuff.

If your products or services are exclusive and limited, some people are willing to pay more for them.

Photographers sell a small set of numbered prints, then destroy the original negative. Fashion designers create new looks for one season, and then retire them.

Rare collectibles go up in price — even if the scarcity is artificial.

Take the Mona Lisa. You can buy a framed copy, printed on canvas, for $60 on Amazon. To the untrained eye, it would look the same as the original, which is worth an estimated $2.4 billion. The reason why it’s worth so much is because everyone knows that there is only one Mona Lisa, and that it is hanging in the Louvre. So no matter how good a reproduction you hang in your basement, your friends probably won’t be impressed.

To make this worth in the virtual worlds, you have to convince people that your product is, in fact, exclusive — and then you have to find people who whom this matters.

I confess, I’m one of those people. I wear virtual clothing on a virtual TV show — Inworld Review — and I am willing to pay extra for unique or rare clothing that everyone hasn’t already seen a million times. But, to be honest, I don’t know where to go to find it! So, fashion designers, if you want me to wear your outfits on the show, email me at maria@hypergridbusiness.com.

6. Raise prices

Yes, over time, with competition, prices do tend towards the minimum costs of production.

But have you ever walked into a wine shop, looking for a nice bottle of wine to bring with you to a dinner party?

If you are a wine know-nothing, like me, you probably started out by deciding how much money you wanted to spend, then picked the nicest-looking label in that price range — or asked the clerk for a recommendation.

Because, like me, you assume that more expensive wines taste better. And the thing is — they do!

If you know how much the wine costs, then your appreciation of the wine rises along with the price. Studies show that people who spend more money on an energy drink do better at solving puzzles. More expensive medicines work better than less expensive ones, even when the ingredients are identical.

Not because they ARE better — in blind taste tests, the effect goes away. But because we THINK they are better. We appreciate things more when they’re harder to get, or cost more money to buy.

If you pick up a $2 T-shirt in a thin fabric with frayed hems and a badly printed design, you’d think, “What a cheap piece of crap. Look, you can see through the fabric, the hems are frayed, and the design isn’t even printed all the way.”

But if the same T-shirt was priced at $200, you’d think, “What delicate, gossamer fabric, and artistically frayed hems. And you can tell the design is hand-made, not printed by a machine.”

If a food tastes bad and is low-priced, it just tastes bad. If the same food is expensive, then it’s “an acquired taste.”

A good story can help make a high price believable. That could be the story of how it was made, or of its special ingredients, or exclusivity, or the personal story of the artist or creator, the reputation of the brand, or even stories about other customers. If my favorite celebrity uses a product, I might be willing to pay more for it — and even more if the celebrity had used that actual product itself.

I’m not saying that you should just make up a story. Customers will get really upset if they feel they were lied to. The reason for the higher price doesn’t have to be a good reason. It can be a very trivial reason.

Airlines charge thousands of dollars extra for a seat a couple of inches wider, with a few extra inches of legroom, a couple of glasses of wine, and a slightly better microwaved dinner. If I wanted to fly to Shanghai tomorrow, I could pay $500 for a regular ticket — or anywhere from $5,000 to $15,000 for a first-class one. Really? Do those extra inches really mean that the experience is ten times better? No. It’s 16 hours in an airplane. It’s only marginally better, not ten times better.

But people buy the seats, and they appreciate those seats. And the airlines make us economy travelers walk past all those nice, wide seats when we get on the plane, reminding us of what we’re missing.

And just in case you feel its morally wrong to overcharge for a product, remind yourself that your customers voluntarily give you their money — you don’t make them. And that the kind of customers who like and can afford to buy expensive stuff appreciate their purchases, and if they weren’t buying your expensive stuff, they’d be buying someone else’s. So go ahead and take their money and if you still feel bad, use some of these excess profits to donate products to people who need it. Schools, for example.

- Analysts predict drop in headset sales this year - March 25, 2025

- OSgrid enters immediate long-term maintenance - March 5, 2025

- OSgrid wiping its database on March 21: You have five weeks to save your stuff - February 15, 2025