When it comes to virtual reality, there are two fronts, two main technical directions that the technology is evolving in that everyone is talking about. But there’s also a third front, that hasn’t been getting as much attention, but which has the potential of being truly revolutionizing.

Videos and video games

One main direction is video-based virtual reality, where cameras such as Jaunt VR are used to create virtual experiences where the users are more-or-less passive participants. They can look around inside a scene, or pause it, but for the most part they’re limited to the kinds of interactions that they have with video content.

For example of video-based virtual reality content, check out Paul McCartney’s virtual concert app, or these three other music-related apps. And read more about Jaunt VR’s immersive video here and immersive storytelling here.

Hollywood has been getting into the act as well with the Game of Thrones and Pacific Rim experiences, X-Men and Sleepy Hollow, the Interstellar spaceship tour, among many others.

Then there are the branded experiences, such as Marriot’s virtual honeymoons or the Volvo test drive or the Merrell outdoor adventure promotion.

The other is video game-style virtual reality, where the 3D graphics are generated by computer and the users can fully interact with the world.

Instead of being a passive participant in a car ride, such as the Volvo VR experience, they can actually drive the car, as if they were in a virtual reality version of Grand Theft Auto.

The former — the virtual reality videos — are typically experienced with low-cost headsets such as Google Cardboard and similar smartphone cases, though the Comic-Con and Marriott experiences used the Oculus Rift for greater immersion. The focus here, right now, is on content creation since the interface is already good enough for passive experiences.

The latter — the virtual reality video games — are dominated by Oculus Rift and similar computer peripherals because they typically require more processing power and interactivity than a smartphone can provide.

Right now, horror games seem to be particularly well-suited to virtual reality, as demonstrated by PewDiePie in the video below.

Other games that do well in virtual reality are cockpit-style games, where the player inside the game is sitting down — either in a spaceship cockpit as in the Eve: Valkyrie game in the video below, or in the driver’s seat of a car, or in a submarine.

Right now, the focus is on getting the user interface right — mice and keyboards don’t work well when you can’t see them, touch screens are out of reach when they’re inside a headset, and moving in a virtual world using a joystick can be nausea-inducing if not done right.

Both the virtual reality videos and the virtual reality video games are dominated by “walled garden,” one-off experiences, typically running in commercial, proprietary environments.

The third front: the virtual reality metaverse

Then there’s a third front, an interactive, social, standards-based, open source virtual metaverse.

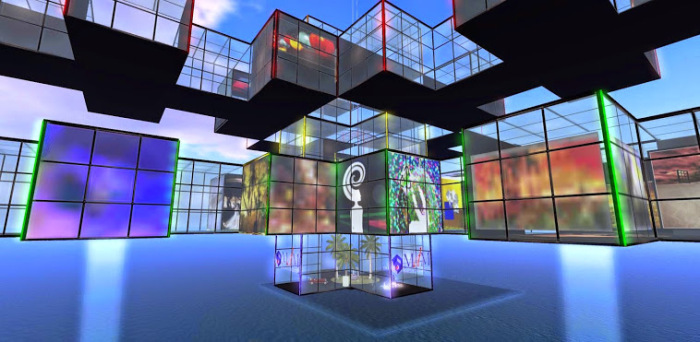

The leader here is OpenSim, which is loosely based on Second Life and allows people to go inside a virtual world and create stuff right from the inside.

It’s Oculus Rift-compatible. Anyone can download the software and create a virtual world. There are also OpenSim hosting companies offering quick and easy virtual worlds, starting at less than $5 per region — compared to $300 for the same region in Second Life.

There are currently over 300 public worlds running on the software, with about half a million registered users total, plus hundreds, possibly thousands more running inside schools, companies, government agencies, and on home computers.

The really amazing thing about OpenSim is that if I have a world, and you have a world, then, unless we specifically lock them down and keep them private, I can teleport from my world to yours with my avatar.

I can send messages to avatars on your world, and move content from your world to mine.

This peer-to-peer, infinitely scalable system is called the hypergrid, and its basically a 3D, virtual reality version of the World Wide Web. Of the 300 public worlds I mentioned, more than 200 are on the hypergrid, meaning that avatars, content, and messages can move freely between them. Well, more-or-less freely — some worlds have some of their content locked down, to keep it from walking away.

For the past few years, OpenSim has been growing slowly, under the radar, much like the early Web did.

As with the early Web, most of the attention is going to go the proprietary, closed platforms at first — the virtual reality equivalents of AOL and CompuServe.

But the advantages of OpenSim — or whatever it eventually evolves into — are much like the advantages of the Web over AOL. The low cost. The fact that it’s open and completely scalable, with no centralized controls or bottlenecks.

An individual can have a little mini-world just for themselves and their friends. A book club can set one up. A roleplaying group. A school. A company.

And the owner of the world has full control over it — who gets to come in and out, what content is on it, everything.

OpenSim’s in-world building tools are relatively easy to use, at least when compared with professional 3D modeling software that other platforms require. And people who don’t have the time, inclination or artistic skills to build their own virtual environments can download free, pre-made content from sites like Zadaroo or buy content from the Kitely Market.

This means that anyone, at any level of technical skill and with any budget, can create and manage virtual environments and share them with friends, family, students, or colleagues.

These environments can be used for socializing or for games. Or for virtual tours, educational simulations, business meetings and conferences, training programs, architectural walk-throughs and other practical purposes.

OpenSim already has a virtual music scene and virtual museums, virtual schools and virtual shopping malls.

Right now, OpenSim is even more cartoony than most virtual reality video games because, unlike video games — but like the Web — OpenSim environments are downloaded on the fly, in real time.

With video games, users download them ahead of time, and then play. The background environment — the landscape, the buildings — doesn’t change, or changes very little, as the game goes on.

With OpenSim — like with a Website — changes can happen at any time. So some content could be cached if you’ve been there before, but, for the most part, it’s all downloaded fresh. That means that graphics have to be lower quality, so that they can be transmitted and rendered with the bandwidth and processing power we have now.

As bandwidth and processors improve, however, OpenSim — or, again, whatever it evolves into — will also become increasingly realistic.

And it will transform our future.

- OSgrid back online after extended maintenance - April 16, 2025

- Analysts predict drop in headset sales this year - March 25, 2025

- OSgrid enters immediate long-term maintenance - March 5, 2025