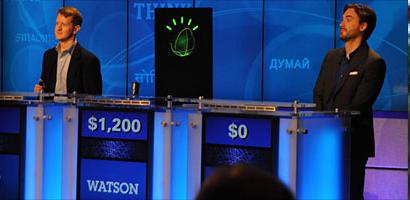

They say it’s not the winning that counts but the taking part. Watson managed to do both — but perhaps the winning actually counted for less. All the indications are that Watson’s win was as much about his — or its — speed on the buzzer as for his knowledge.

As competitor Brad Rutter said, “On any given night nearly all the contestants know nearly all the answers, so it’s just a matter of who masters buzzer rhythm the best.”

So the impressive thing is that Watson had sufficient knowledge to be a credible contestant, the winning was secondary.

While of course the sheer power of the computers involved and the man-decades of development count for a lot, the real key to Watson’s success was in its use of semantic markup. Most chatbots (of which Watson is a specialized type) rely on matching an input pattern against a database of possible pattens, and then returning the response programmed for that pattern. This is how Pandorabots (much used in Second Life) work, and to an extent our own Discourse system. The problem is that this approach does not scale, and the bot “knows” nothing — it just matches characters.

With a semantic approach the bot has a web of knowledge. The most pure way is to use triples, very simple relationships between an object (“sea”), an association (“has colour”), and a subject (“blue”). When these elements are then linked into an ontology of things (blue is a colour, sea is made of water, sea is a habitat, sea is a geographic feature) then the bot can begin to make deductions and links between the words in the input text.

This means he can deduce the things that the question might be alluding to, and try and map that to an answer. Watson is not the first chatbot to use semantic markup (we’ve also  been doing similar things since 2008 but just not with IBM’s resources — see our Halo  bot talking about ants and stars), but we are in no doubt that semantic representation will be key to chatbots in the future.

As to whether Watson is the future and represents a great leap for artificial intelligence, it all depends on what you are looking for. If you see AI as being about god-like bots, Terminator’s Skynet, or, more prosaically, expert systems, then yes this is a step forward. Wolfram Alpha was one step towards the “global answer engine” (but Google and Wikipedia more so), and Watson is another step. But these are brute-force solutions to brute-force problems.

One of the truisms of machine intelligence is that as long as a machine is unable do a particular task, people say that the task requires intelligence. But once the machine can do it, then they say that the task didn’t need intelligence after all. Chess is a good example. Once seen as almost the best measure of an “intelligent” person, after Deep Blue beat Kasparov in 1997 chess was seen as more of a brute-force problem, and no one claimed that Deep Blue (or the chess app on your smartphone) was intelligent.

The issue is that Watson is an “answer engine,” not a “conversation engine,” and definitely not an “artificial general intelligence.”

Trying to mimic the flow of human conversation is something that still appears to be beyond our reach, and for this Watson is actually heading in the wrong direction. Human conversation is often very imprecise, even inaccurate, but it flows. If I asked Watson what 16,353 times 9,543 was he’d probably know — but most humans wouldn’t. In creating more “human” bots we actually find we have to try and dumb the computer down.

For example, in a virtual world we don’t want our bot to say “you are at 123.2, 31.42, 78.12,” but rather “you are standing on my foot,” or “you’re a couple of feet from the door.” While giving IBM credit for their achievement with Watson, I’ll personally be more impressed when IBM create a believable four-year-old rather than a Jeopardy champion.

These two paths, towards a global answer engine, and towards an analogue of a “real” human, are both valid, and to an extent connected, but they are different paths. And I feel that humantity will be more challenged ultimately by the possibilities of the latter than by Watson and his descendants.

- Four major types of virtual reality - February 21, 2016

- Getting to grips with High Fidelity - November 7, 2015

- 5 key differences between virtual worlds and virtual reality - August 1, 2014