[Editor: A couple of years ago, Chris Ravensoft was an actual paying customer for Second Life Enteprise, a behind-the-firewall version of Second Life, designed for companies who needed a secure, private space for internal collaboration, training, and rapid prototyping. In the summer of 2010, Linden Lab shut the project down.]

How bad was Second Life Enterprise?

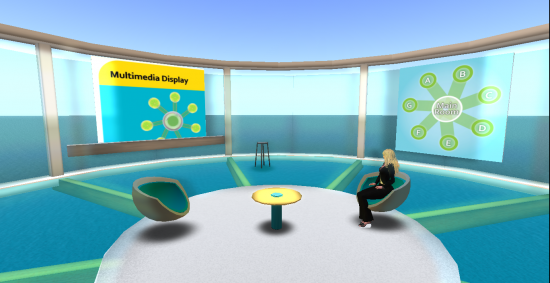

I have had positive experiences with virtual environments in an enterprise setting. But in this column, I’d like to talk about one project that did not work out for us.

Second Life Enterprise was a failure, in my case, for several reasons. Note that this experience is my own, maybe other beta users had a better one. Linden Labs announced the end of the experiment in August 2010.

Let’s see what really did not pan out despite the promises of the platform.

Ideal conferencing – not

Features that would really have brought it closer to the ideal conferencing tool were still far in the future.

Face capture and embedded video feed would have allowed other users to measure one’s state of mind through their facial expressions.

We were sold on the idea when we saw a cool video of Ashton Kutcher’s face mapped to this avatar’s “head†showing him interact with Second Life and expressing obvious delight at what he was seeing.

Another feature we would have liked to see was seamless integration with Microsoft Office — what a leap in the future this would have been! The only alternative available when giving a presentation using Powerpoint was to take screenshots of every slide, convert them using suitable jpg settings, then map them as textures to wall surfaces in Second Life.

Supposedly, this painful exercise was about to become a thing of the past “anytime soon.â€

Not worth the cost

“Cost†can be interpreted in – at least – two different ways, both of which apply here.

First, the entry cost to simply be a part of the beta, was between $50,000 and $100,000. For the first year.

For that money, you would receive two servers and access to an online help desk. Tickets only.

Second, the ownership cost was just too high. So many prerequisites would pop up as we progressed through the setup process that I reached a point when I became quite convinced that the Linden people had never talked to anyone who works in a big company. I could not imagine a use case that their process would satisfy.

For example, customers did not get root access to their Second Life Enterprise machines — that part I can understand. However, in order to perform simple configuration, I needed to be able to get our IT department to poke a hole for incoming SSH sessions in our firewall at the most random times. The Linden gremlins would then come in through this wall and type whatever one-liner was required.

Next, software upgrades were performed by swapping the existing hard drives with new hard drives they sent in the mail. In order to perform the swap successfully, I needed to work with our IT guys to have unfettered access to the data center for two days. Alternately, I could ask for an IT guy’s time to be dedicated to this task for two days. The Linden people expected us to have someone continuously available to be on the phone with them as the upgrade went through.

>Note that, even if I did the upgrade myself, basic security rules required for IT personnel to be present in the data center at the same time as a non-IT person –me! We originally thought this would be a non-issue as the tool was being marketed as a “turnkey†solution.

Then, support tickets could go unanswered for days and, in some instances, weeks. After several weeks of this frustrating dance, I finally realized what was going on: they were using the same ticket system for both enterprise customers and public grid Second Life users. Now, I do not know what their triage policy was but considering the delays in getting any kind of reply, I suspect it was not what an enterprise customer would have expected.

I was not trying to do anything fancy. I just wanted to get the servers up — which I eventually did — and run a few grids. Some of my basic questions left them dumbfounded. Questions I would have expected other beta testers to have asked as well.

Finally, there was no tool was available to automatically export our existing builds on the Second Life public grid and import them to our private grid. Instead, we had to compile a full inventory of every single prim, mesh, texture, animation, and so on, and send them this list along with proof that we had all the copyrights cleared for all of them. They would then, after an indefinite period of time, send us an archive containing, hopefully, our stuff.

That’s when I started looking into the banned tools that some enterprising users had created to “steal†content and transfer it to OpenSim — or sometimes for quite shadier purposes.

Irony

An important aspect of owning our private grid was using it to provide training to our customers. We already had at least one major account asking for virtual training since it would allow us to train geographically dispersed technicians. We were also considering the potential for internal training and this was obviously the first direction we would have taken the grid’s design.

Unfortunately, educational tools such as Sloodle were only available for OpenSim, the competing free and open-source virtual world platform.

Worse, Linden Labs added a paragraph to their Second Life Enterprise agreement that stipulated that we could only use the grid internally, which meant keeping customers’ employees off the grid. I talked to the salesperson about my concern with that clause and got verbal assurance that we would not have to worry about it. The agreement was not amended, though.

That’s when I decided that it was definitely not worth it.

The aftermath

It is now obvious that Linden Lab’s proverbial heart was never really in the whole endeavor. Unfortunately, this means that the technologies I listed earlier, such as real-time face capture and seamless office integration, were never deployed in the enterprise.

Instead, we spent time and resources attempting to set up a product that did not offer the minimum set of features that would have benefitted our company. Linden Lab, likely realizing that they had waded in quicksands they knew or cared little for, threw the towel not long after I had decided to cut our losses.

An interesting take away lesson here is that, had we gone with an open-source alternative, we would now be working with a product that’s more current, was not end-of-lifed and for which plenty of support is available. And the return on investment would be, in comparison, astronomical.

(This column adapted with permission from Nexus.)

- Second Life Enterprise was a costly mistake - March 21, 2012