With all the hype surrounding the Oculus Rift and similar devices, there’s a lot of speculation in the media — and in the comment streams associated with that media — about whether virtual reality will or won’t replace the real thing.

On the one hand, you’ve got the folks who think that virtual reality will replace movie theaters, walks in the parks, and personal relationships. On the other hand, you’ve got the folks who think it’ll be a niche core gamer market because of the lag, the nausea, and the lack of situational awareness when you’ve got that thing on your head.

Both sides are missing the point. The proponents, by not realising that virtual reality will not replace actual reality, but will be an addition to actual reality. And the opponents for not realizing that technology evolves pretty quickly, and the problems they bring up won’t be around much longer. In fact, the latest version of the Oculus reportedly deals with the nausea issue very well.

Old mediums are hard to kill

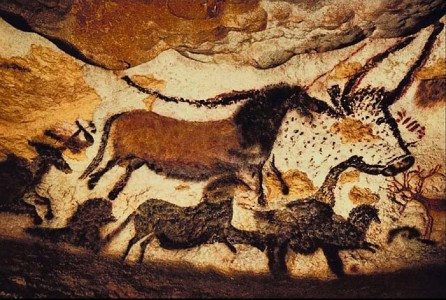

Remember when we had cave paintings? And we all got all cave walls done? And then that guy went and invented sculptures, where you didn’t just sit and look at the thing, but could walk around it, and hold it?

Did we all give up on cave painting? No. We still have art on our walls.

Remember when we all used to sit around the campfire and tell stories? Then books came along and young people just weren’t as interested in story telling anymore and people stopped talking? No? You still sit around each night as your favorite late-night talk show hosts tells jokes? You troglodyte, you.

Or when radio came along and we all stopped listening to live music? Or the way the motion pictures killed the theater industry? Or the way television killed the movie theaters?

Right. None of that happened. We still paint, we still sculpt, we still have radio and movies and even books.

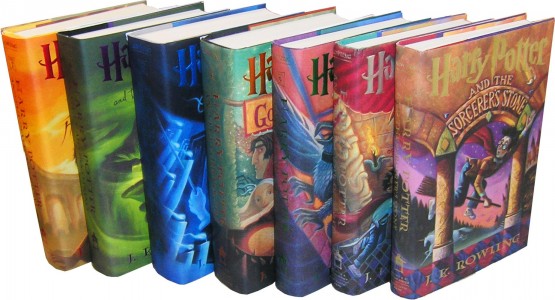

Who would have thought that kids today would have eagerly read a 4,000-plus-page book series set in England? And would have queued up on release night to get their hands on the next book in the series?

I remember taking my daughter to the local bookstore for book release parties. The store was packed. There was a line to get in. There were costume contests and prizes.

In this age of video games, of television and movies, of instant gratification, kids are still willing to sit down and read big, thick books. There’s hope for the future, yet.

Copies do not devalue the original

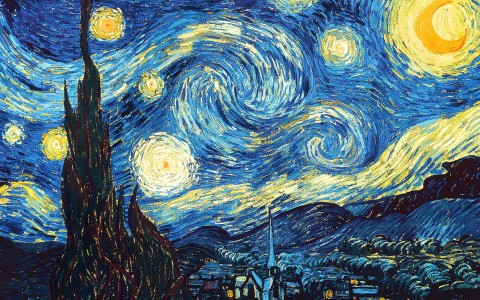

I haven’t been in a college dorm in a while — okay, not since I dropped my daughter off a couple of months ago — but I remember when a print of Vincent van Gogh’s “Starry Night” was on every dorm room everywhere.

As a reminder, for those of my readers who have lived in a cave all their lives, this is what the painting looks like:

You can download a copy of the picture, print it out, and put it up on your wall, for free. Well, for the cost of paper and printer ink.

Okay, that’s not quite the same as the original. It will look like a cheap printout. So you can buy a poster of it for $4.99. Put the poster in a frame, step back a little ways, and you won’t know the difference from the real thing.

Still not good enough? Buy a copy printed on canvas, starting at $33.00. You won’t be able to tell the difference between it and the real thing unless you’re an expert. Put it under glass and frame it and not even the experts will known for sure, though they might suspect due to the fact that it’s hanging in your basement and the original is hanging in the Museum of Modern Art.

But the original painting is still worth an estimated $100 million and people get in line to see it.

The fact that indistinguishable copies are widely and cheaply available does not diminish the value of the original painting. Instead, by creating mass awareness of it, the value of the unique original only increases.

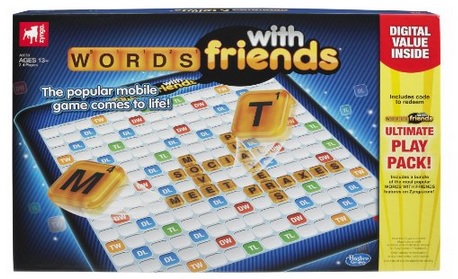

My favorite example of this is the game Words with Friends, a cheap app knock-off of the original Scrabble. Scrabble, presumably, didn’t release an app to avoid devaluing the brand. Ironically, Words with Friends became so successful that there is now a real-world version of the game, the Zynga Words With Friends Classic Game.

To take another example, artificial diamonds are so close to the naturally-occurring ones that the diamond merchants have to laser engrave the real ones with with serial numbers to prove that they’re not man-made. But if you propose to your would be spouse with a $5 ring only a very, very small minority would admire you for your thriftiness.

And even the most pragmatic would be embarrassed to show the cheapo ring to their friends without an explanation that the two of you are putting the money towards your house, or towards travel, or your kids’ college tuition, or donating it to protect the natural habitat of honey badgers.

And it’s not the same. Nobody ooohs and aaahs over a $5 ring, no matter how indistinguishable it is from the real thing.

Of course, there are also plenty of examples where a new medium has completely or almost completely destroyed the previous version. Telephone books, dictionaries, encyclopedias, reference books of all kinds immediately come to mind. Film cameras are almost completely gone, as are video tapes. Print newspapers are on the way out.

So what is the difference? Why does the virtual replace some physical things, but not others?

Here are three factors that can doom a product to the dustbins of history.

No pride of ownership

Are you proud to own a telephone book? Are you proud of the stacks of old newspapers all over the house? Are you proud of your collection of old VHS tapes?

Pride of ownership is something that’s difficult to quantify, but everyone immediately knows it when they see it.

I am not proud of my collection of generic supermarket mysteries. But I am proud of my signed, first-edition Ray Bradbury book. I’m going to donate the mysteries to my library’s book sale, and I keep the Bradbury on a glassed-in shelf so my cats don’t eat it.

When you move, do you tear down the posters from the wall and throw them away? If so, at some point you’ll probably replace them with digital picture screens. Or do you carefully preserve them?

I am proud of my old photo albums and like looking through them, and showing them off to people. I wish I had a better way to print out the digital photos I’m taking now.

Since pride of ownership is an emotional thing, there are lots of factors that could affect it. My own photos are more valuable to me than someone else’s, even if their photos are prettier. An object with a story behind it is more valuable than the identical object without one — like, for example, clothing and props used in movies, or baseballs caught at a game, or jewelry that’s been owned by royalty and has curses attached to it.

Pride of ownership extends to experiences, as well.

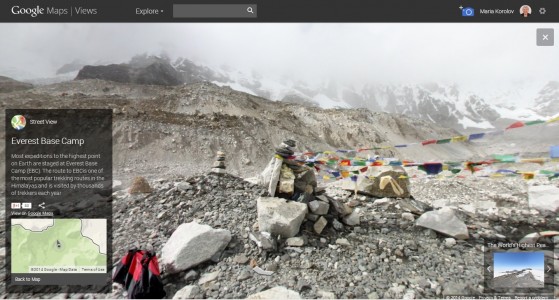

Are you proud to have climbed Mt. Everest? If you did, you probably find a way to slip it into every conversation you’ve ever had.

Are you proud to have toured Mt. Everest on Google Earth? Do you tell your grandkids about it? Well, if you have grandkids, you might be proud of the fact that you figured out how to use Google Earth, but that’s a different kind of pride.

No significant distinguishing features

This is another one that’s hard to quantify, but we all know it when we see it.

A printed dictionary is obviously different from an online dictionary. It’s made of paper, it takes up room on a shelf. You can hit someone with it or use it as a paper weight. But the basic functionality is identical to its online version, except that it takes longer to look things up, it can go out of date quickly, and that there’s a limit to how many definitions it can hold.

A VHS tape has no positive significant distinguishing features compared to a DVD. All it has is bad ones, like lower quality.

A trek up Mt. Everest has quite a number of significant differences from that of touring it virtually. Some are disadvantages — price, time commitment, risk — but those seeming disadvantages all contribute to the pride of having completed the experience.

There are advantages, as well. The sense of camaraderie with other members of your team. The feeling of accomplishment. The joy of knowing that you’re a better human being than your brother-in-law, who never goes anywhere.

Another distinguishing feature is intent, which applies to interactions with people and animals. A dog is genuinely happy to see you when you come home. A virtual dog may appear to be happy, but you know that it’s just a trick of animation. Your friend is genuinely happy to see you and actually means it when they ask how you are. When a fast food restaurant clerk asks the same thing, you know it’s probably just good training.

It still feels good when a clerk smiles at you, or when your virtual pet greets you, but you know that there’s no personal intent there, even if the experiences seem to be identical on the surface.

In “The Third Aunt from the Sun” episode of Sabrina: The Teenage Witch, Sabrina visits her Aunt Vespa, who lives in the Pleasuredome. Despite having everything she could possibly want, whenever she wants it, it turns out that Aunt Vespa is desperately lonely, and turns to a closet full of empty compliments to cheer herself up.

The entire episode is well worth watching as a preview of what virtual reality could be like, and is available for free on Hulu.

Commodification

One of the things that makes say, the Mona Lisa, so valuable is that it is unique. There is only one original Mona Lisa, and it hangs in the Louvre.

What makes poster prints of the Mona Lisa almost worthless is that they are so common. If your Mona Lisa poster gets a rip in it, you’ll throw it away without a thought, regardless of the quality of the underlying art. Why not? You can just go out and get another one.

Professional photographers create artificial scarcity by issuing only a limited number of prints. Artificial scarcity can also be created through the use of copyright, high prices, and limited distribution channels. Artificial scarcity is why diamonds have any value at all, since they are naturally pretty plentiful.

A similar approach can be used in virtual reality, with content designers creating artificial scarcity through limited-edition collections, high prices, or exclusive access.

A telephone book is an example of a physical product that is not only plagued by a lack of pride in its ownership and a lack of distinguishing features, but is also completely common. Everybody has a copy. Until, of course, the phone books become so rare that they become collectors’ items.

A mass-produced game is another example of something common that may be moved into digital form. Then, once it becomes rare, the original physical product becomes valuable.

- OpenSim activity up with the new year - January 15, 2025

- OpenSim land area, active users up for the holidays - December 15, 2024

- Discovery Grid moves from OpenSim to O3DE alternative - December 15, 2024